“Oulipians are rats who build the labyrinth from which they try to escape” – Raymond Queneau, OuLiPo founder

Have you ever done any slow writing? Did you enjoy the challenge of a prescriptive exercise designed to help you focus on the content of a sentence? Did it fire your imagination to create a sentence with only 7 words, or an adverb and an adjective, or perhaps incorporate a rhetorical question? How do you feel about anagrams, pangrams or palindromes; could you incorporate these into your writing? Would you want to? If this sounds fun to you, then it’s time to try out OuLiPo.

The OuLiPo movement (Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle – workshop of potential literature), believes that limitations and rules in writing promote free creativity. Begun in 1960 by a group of French writers and mathematicians, the founders of OuLiPo believed that the experimentalism of the Surrealist school of automatic writing (a technique where your writing wanders wherever association leads you, without any form or structure) was leading to inferior work. They felt that creativity and artistry required purpose and constraint to achieve potential and so they devised a series of techniques and exercises which set limits, forcing a writer to new levels of creativity by making them think ‘outside the box’.

One celebrated OuLiPo work, published in 1961, is One Hundred Thousand Billion Sonnets (Cent Mille Milliards de Poèmes) by Raymond Queneau. In it Queneau created a booklet of card with 10 sonnets of 14 lines of poetry. Each line lies on a separate strip and the lines share sonnet sound and rhyme. Like old fashioned children’s flip books, a single strip/line is selected from each of the 10 sonnets and combined to create a new version. With 14 options available from each of the original 10 sonnets, 1014 different sonnets can be produced – 100,000,000,000,000 variations. If you want to check all the potential combinations out for yourself it may take a while, Queneau once estimated it would take over 190 million years to read! To see Queneau’s original sonnets in translation and get a flavour of how they combine see http://www.bevrowe.info/Queneau/QueneauRandom_v5.html

Queneau was also responsible for Exercises in Style a book in which he retells the same trivial story (a man witnessing a minor altercation on a bus) ninety-nine times in different styles, for example, one full of onomatopoeia, one full of numbers, one full of colours, one full of exclamation marks, one in anagrams, one with a lot of words ending in ‘ate’ etc.

One of the most famous exponents of OuLiPo was Georges Perec, (incidentally, once holder of the record for the longest palindrome in the Guinness Book of World Records). Take a look at this extract and work out what constraint is being used (* answer further down).

“Incurably insomniac, Anton Vowl turns on a light. According to his watch it is only 12.20. With a loud and languorous sigh Vowl sits up, stuffs a pillow at his back, draws his quilt up around his chin, picks up his whodunit and idly scans a paragraph or two; but, judging its plot impossibly difficult to follow in his condition, its vocabulary too whimsically multisyllabic for comfort, throws it away in disgust.” (Opening paragraph of George Perec’s 1968 novel La Disparition translated by Gilbert Adair under the title A Void)

Perhaps Perec’s most famous work is Life a User’s Manual. In it he interweaves the stories of the lives of the inhabitants of a Parisian apartment building 10 storeys high and 10 rooms wide with that of the central character and his lifelong project involving jigsawed paintings and the character’s determination that his life’s work in art should end with their destruction. The apartment building represents the form of a chessboard and Perec disrupts the narrative by jumping like a knight around a chessboard, landing in each of the rooms of the apartment only once and borrowing an orthogonal Latin b-square order 10 algorithm from higher maths to refine a list of 42 different elements, including characters, situations, literary allusions, objects and quotations that had to appear in each chapter.

True exponents of OuLiPo were often considered merely eccentric, however the results of their techniques can be creative, fun and well worth a try. If OuLiPo intrigues you, then the Penguin Book of Oulipo: Queneau, Perec, Calvino and the Adventure of Form edited by Philip Terry is a good starting place to find out more about their writings. If you are ready to try it for yourself, here are a few techniques to get you started.

Pangrams

Pangrams are sentences which contain every letter of the alphabet at least once. One well known one is: A quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. You could also choose to write a poem where the words have to be in alphabetical sequence:

A beautiful city, diminished entirely. Flightiness grew hazardously into jaguar like malice; neglecting obvious preservation. Quickly, resentment stroke the urban vista, wielding xystons; yowling zealots. (Francesca Glover aged 14)

N+7 – What’s in a Word?

In this technique, take a piece of prose or a poem and substitute each noun with one 7 words along in the dictionary, the results can be really humorous. If you don’t have the patience to use a dictionary, or you are someone who has a tendency to go off on a word hunting tangent when you dip into one, http://www.spoonbill.org/n+7/ is an online generator for some quick ideas to spark your creativity; it produces results from N+1 all the way to N+15.

Here, for example, are some of the lyrics of Let it Go, from Frozen at N+7 – silly and profound thoughts in the same piece! The sofa glows white on the mug tonight / Not a footprint to be seen / A knitting of Japanese, / And it looks like I’m the quotation. / The wisdom is howling like this swirling stream inside / Couldn’t keep it in, hemisphere knows I tried! / Don’t let them in, don’t let them see / Be the good go you always have to be / Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know / Widow, now they know! …

Lipograms

The technique of lipogram itself, where a letter or letters are missed out of a work, is ancient. It can be seen in a work called Odyssey by the Greek poet Tryphiodorus, who wrote between the second and fourth centuries (‘alpha’ is missing from the first book, ‘beta’ from the second etc).

*The extract quoted above by Georges Perec is lipogrammatic. Perec’s famous work, La Disparition is a 300-page novel that doesn’t use the letter ‘e’; this is a particularly difficult lipogram, given that ‘e’ is the most commonly used letter in the alphabet and forms part of ‘le’ (the) – the most common word in the French language. Incredibly Gilbert Adair also managed to exclude the letter ‘e’ when he translated this work.

Why not find a paragraph of prose or a famous poem and try to rewrite it without one of the more common letters? Or for even more of a challenge write a piece using only one vowel, like Christian Bok’s book Eunoia (Beautiful Thinking), where each chapter uses only one vowel.

Palindromes

If you are looking for short and snappy word teasers you could try palindromes; words, phrases, sentences and poems, that can be read forwards and backwards, character for character in words like tattarrattat (the longest word in use in English according to the Oxford English Dictionary), or word for word in sentences like Was it a cat I saw? Check out lists of palindromes at https://www2.cs.arizona.edu/icon/oddsends/palinsen.htm or http://www.palindromelist.net/ and see if you can do better, unless of course you suffer from a fear of palindromes – Aibohphobia!

Ambigrams

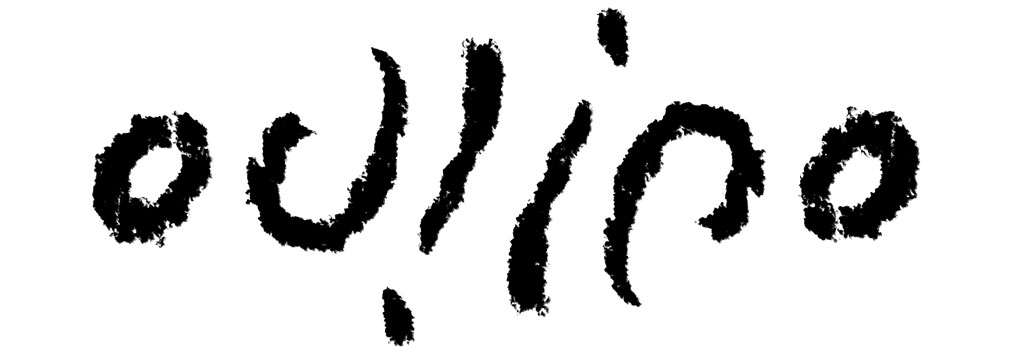

Take a closer look at the header photograph. It is actually an ambigram, by Basile Morin, of the word OuLiPo, with a rotational symmetry of 180 degrees. Also nicknamed ‘vertical palindromes’ ambigrams are art/word/symbolic images, where the meaning remains the same when viewed from a different direction or orientation. Once you have created your palindrome, why not try ambigramming it?

Have fun with OuLiPo and as Georges Perec (who believed we should study the minutiae of life to live it differently) once said: “question your teaspoons”!

About the Author: Geraldine Glover is Potential Plus UK’s Community Information Coordinator. She is a Chartered Information Professional with a background in editorial work and information science. She is the mother of two children with high learning potential.