So many young people have had prolonged interruption to their school life. It’s timely to return to resilience. Our learners need to be resilient to cope with this disruption and its concomitant impacts on anxiety, wellbeing and achievement.

Resilience can be nurtured or destroyed over time and is closely linked to a learner’s determination and intrinsic motivation. It is obvious that resilience is much in evidence as a baby learns to walk. However, for learners with high potential, it is easy for teachers – or anybody – to say the wrong thing, at the wrong time, with the best of intentions and erode that resilience.

This blog considers:

- Definitions of resilience

- The research which underpins current thinking about the development of resilience, including a brief recap of the work of the psychologist, Carol Dweck (familiar to most of us)

- Process v person praise

- The sweet spot: the conditions and support needed for resilience

- Practice v perfection

- Strategies for teachers to use to foster resilience in high potential learners.

Definitions of Resilience

- The capacity to recover quickly from difficulties; toughness. The ability of a substance or object to spring back into shape; elasticity. Oxford English Dictionary

- If someone is displaying resilience, two elements must be present: namely, adversity… and successful adaptation/competence. Luthar et al. (2000)

As the definitions stress, the capacity to bounce back from setbacks, wherever they come from, leads to resilience. We may conclude that this is essential to building confidence, wellbeing, academic success and continuous improvement through embracing challenge.

Why Resilience Matters: the Research

There are wide-ranging and significant benefits to developing resilience. Learners who develop good resilience benefit by…

- Seeking out better feedback, stretching themselves and persisting for longer (Muller and Dweck 1998)

- Coping better with transitions (Blackwell et al. 2007)

- Higher levels of grit (Hinton and Hendrick 2015)

- Securing better grades and being less likely to drop out of school (Pauneska et al. 2015)

- Reduction in stress and aggression (Yeager and Dweck 2008)

Quick Recap of Carol Dweck’s Research

Carol Dweck is probably the best-known psychologist in this field. She continues to reflect on her work on mindsets as it has been used widely and, sometimes, without nuance. It is important to understand what her research does NOT claim, just as it is important for us to understand what it does mean for our learners.

A summary of Dweck’s’ fixed and growth mindsets.

Fixed Mindset

- A belief that intelligence is fixed or inherited and there is little you can do to change it

- If you have high learning potential, you are fortunate

- Learners are motivated by looking smart and by avoiding situations which may hint at lack of ability

- Avoid risks or challenges unless they can guarantee success

- Feel smart when they get good marks and outperform others

Often panic and underperform when the learning is challenging

Growth Mindset

- A belief that everyone can develop their intelligence and skills with practice and the right support.

- Not concerned about looking smart

- Thrive on knowledge

- Motivated by learning something new

- Viewing mistakes as learning opportunities

- Focusing on self-improvement

- Welcoming challenge to improve their learning

- Understanding that struggle is a part of learning

Don’t Throw the Baby Out with the Bathwater

Many educationalists rightly challenge some of the concepts claimed by proponents in relation to growth and fixed mindsets. Growth mindset does NOT mean that everyone just needs to practise and persevere to become an expert. Everyone can improve. For example, a person could practise and practise running and get better but few will become good enough to compete for the UK at sprinting.

Similarly, sometimes practice is not enough. Children need teacher intervention to improve and to learn new strategies. Being told to, ‘keep trying’ isn’t necessarily going to get you there.

People will also demonstrate different mindsets in different situations. For example, in the classroom, you may well have a growth mindset and constantly seek new ways to teach. Yet, in a different situation, such as leading an assembly to the whole school, the same teacher may demonstrate the traits of a fixed mindset.

Crucially, from an early age, teachers can have an enormous impact on the positive development of a mindset which welcomes challenge and sustained self-improvement.

Despite the ongoing debate, there is much in Dweck’s work that is valuable for the classroom and she continues to evolve her understanding through research.

Process Praise v Person Praise

An interesting piece of research, by Gunderson, showed that boys receive more than twice the amount of process praise (about learning skills) than girls, who are far more likely to be praised as a person (praise for outcomes).

This is doubly difficult for girls with high learning potential. As a generalisation, girls are likely to develop some skills earlier than boys. For example, their fine motor skills development may mean that their handwriting is significantly better earlier. This coupled with the fact that they are cognitively ahead of their peers, makes it likely that they will hear the words, “What a good writer you are. Lovely, neat handwriting.” The message here is that you are interested in them producing ‘lovely neat handwriting’ and not on the thought processes or development of the content that they are actually writing.

The Sweet Spot Needed for Resilience

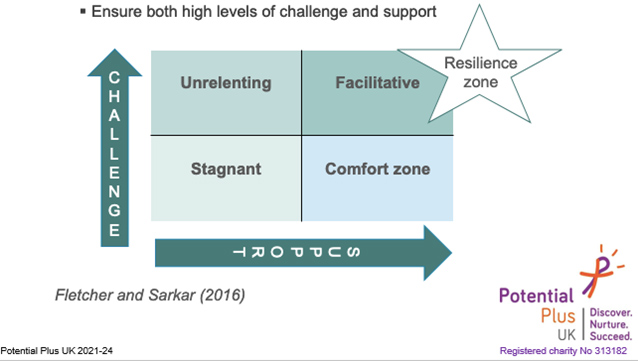

To nurture resilience, learners need both support and challenge. Little support and minimal challenge results in the learning and skills development stagnating.

The long-term consequences of staying within a comfort zone with plenty of support yet little challenge, is to stagnate rather than to stretch themselves. This easily leads to perfectionism as learners repeat and repeat rather than grow and develop. When they do eventually hit high levels of challenge academically or at work, learners won’t have developed the necessary coping strategies.

The learner who receives a great deal of challenge, day after day without the support needed to learn new strategies and skills, will soon feel overwhelmed as the work will seem unrelenting and stressful. This group will be at risk of giving up when they come across setbacks, as they have no back up strategies to get themselves unstuck.

High levels of challenge and high levels of support is the segment of the grid to aim for. Having access to challenging learning with the teacher scaffolding as needed, until they are able to complete the task independently, will ensure that they continue to learn effectively. This is the sweet spot where resilience happens.

The Value of Practice v Perfection: 50lbs of Clay Experiment

In 2001, David Bayles carried out an experiment to find out what would have the better outcome – focussing on perfection or on practice. He divided college students into 2 groups and gave each group a different instruction. Group1 was told to make 1 pot in the time available. It needed to be a perfect pot and they would be graded on the technical skill, accuracy and its aesthetic qualities.

Group 2 was given a very different instruction. They were told that they would be graded simply on the number of pots they produced in the given time. It didn’t matter what the pots looked like, how technically accurate they were or how pleasing to the eye. The mark was to be based entirely on quantity.

At the end of the experiment, group 2, the group who were told that their grade would rest on quantity, outperformed the first group in every aspect of quality. Their pots were more technically proficient, more attractive, evenly shaped, fewer mistakes or defects. The group aiming to make a perfect pot had not benefited from trial and error, hadn’t had the same amount of practice and were hampered by having to strive for perfection.

The ‘50lbs of clay experiment’ is a good one to discuss with a perfectionist! It reinforces the importance of strategic practice and marginal gains, particularly important for high potential learners with a fixed mindset in some aspects of their learning.

Fostering Resilience in High Potential Learners

Common issues for high potential learners in the classroom

Becoming an early expert and then sticking to the method that you know.

Suggested response for teachers

“I can see that you know that method well. Let’s try a different problem that needs a different method so you’ll know two strategies to use in different situations. Then you’ll be able to choose the best one.”

Learned helplessness: repeated struggle without any progress can lead to a learner believing that the task is hopeless. For fixed mindset high potential learners this can become entrenched and generalised.

Notice this early and intervene. Provide strategies, live modelling, step-by-step support and lots of process praise for perseverance and attempting new methods.

Coming up against an obstacle when learning has previously been easy for them so that they do not know how to get unstuck.

Avoid words like difficult, challenging or hard. Use ‘tricky’ as tricks can be worked out. Then move to step-by-step strategies to work through the obstacle collaboratively.

Consistently getting high marks which can lead to perfectionism.

Full marks can be greeted with, “Oh apologies. I wasted your time. Let me find you something to stretch you further”.

Producing beautiful outcomes.

Praise the process, not the outcomes. “Your use of light is so powerful. Talk me through how you created this effect” or “I noticed you trying out a few strategies to get it right. That’s great. Tell me about your choices”.

Seeking perfection. Spending far too long on a piece of work which may mean running out of time to complete the bits that do matter. This is a big problem in assessments/exams.

Remind them it’s not heart surgery and will not require that level of precision. To help: provide plenty of timed practice; use activities around prioritising information; clarify the level of detail required; provide separate opportunities to explore their interests in more depth (e.g. as home learning projects).

Underestimating their capabilities resulting in spending too much time on the wrong things or when a break would be more beneficial.

Move them to an understanding of where there are gaps in knowledge or understanding, e.g. using past papers. Be directive about where the focus is needed.

Avoiding tasks unless they can guarantee success.

Praise learners for taking on more challenge, giving it a go, persevering. Weight the feedback towards the processes, not the outcome.

Disliking their mistakes and/or hiding them.

Model coping with mistakes. Welcome your mistakes, and the class’s mistakes as a great opportunity to learn and correct misconceptions.

Blaming external factors for failures, e.g. “We didn’t learn that in class”.

Help them to see what is in their control and, therefore, their responsibility. Encourage them to transfer knowledge to new situations. “How might you apply what you have learnt to this question?” It’s going to be really important to learn how to do this for secondary school / Sixth Form/ university.

Unwilling to give an answer unless they know it will be right.

Insert, ‘might’ into questions. “Why might the plague have spread so fast?” You may also say, “I’m interested in your thinking, not just in a correct answer”. Provide discussion time before taking responses.

Focuses on the mark achieved for each piece of work and ignores the comments.

Don’t give them a mark! Just provide comments and talk about next steps.

References and Further Information

- Dweck, C. (2017 updated edition). Mindset: Changing the way you think to fulfil your potential. Robinson

- Dweck explaining the effects of praise https://youtu.be/TTXrV0_3UjY

- Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2016). Mental fortitude training: An evidence- based approach for developing psychological resilience for sustained success. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 7(3), 135-157

- Gunderson, E., Gripshover, S.J., Romero, C., Dweck, C.S., Goldin-Meadow, S., Levine, S.C.. (2013). Parental praise to 1-3 year olds predicts children’s motivation framework 5 years on. Child Development, 1-16

- Luthar, S.S., Cicchetti, D., Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience. A critical evaluation and guidance for future work. Child Development 71, 543-562

- Bayle, D., & Orland, T. (2001). Art and Fear. Image Continuum Press (free online library)

Free mindset test

- Mindset test https://blog.mindsetworks.com/what-s-my-mindset

About the Author: Mary Phillips: Potential Plus UK Schools Advisor

Mary was the Head of English before moving to Yorkshire to set up her own consultancy, specialising in education. She works with senior leaders and classroom teachers as a coach and mentor. She facilitates a wide-range of professional learning and has lived experience of the challenges and joys of living with a child with high learning potential.

About the Author: Joy Morgan: Potential Plus UK Trustee

Joy was a senior leader in London schools until August 2021, responsible for professional learning and for high learning potential. She has helped many schools to develop their policy and to improve their practice for high potential learners. Joy is passionate about securing excellent outcomes for disadvantaged learners. Her extensive experience within schools is invaluable to the team. Joy continues as a Trustee of Potential Plus UK.