This article was written by a Potential Plus UK volunteer who wishes to remain anonymous.

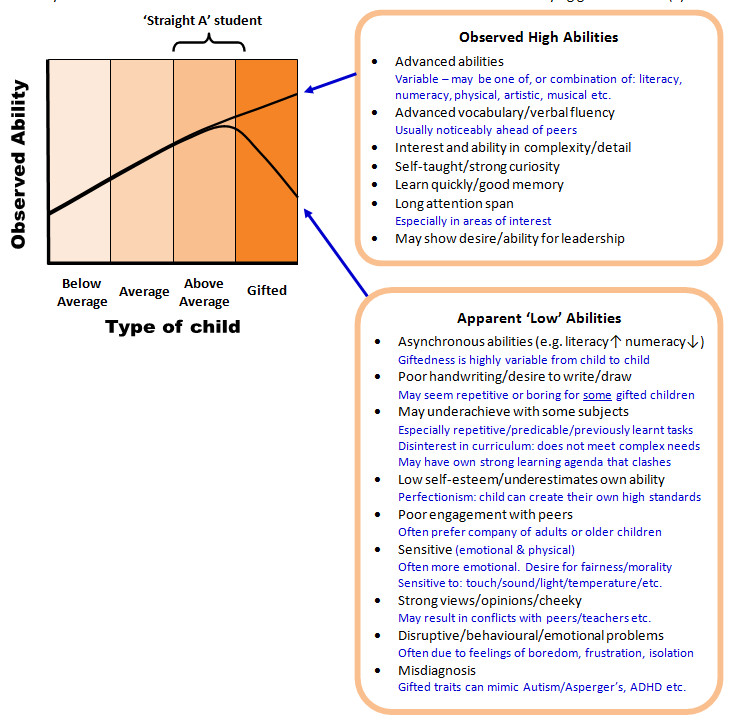

The above average ability child found in most classes, may often appear to be a ‘Straight A’ student who does well across a range of subjects and be socially well integrated with their peers. They may also often be assigned gifted and talented extension activities in the form of enrichment or acceleration.

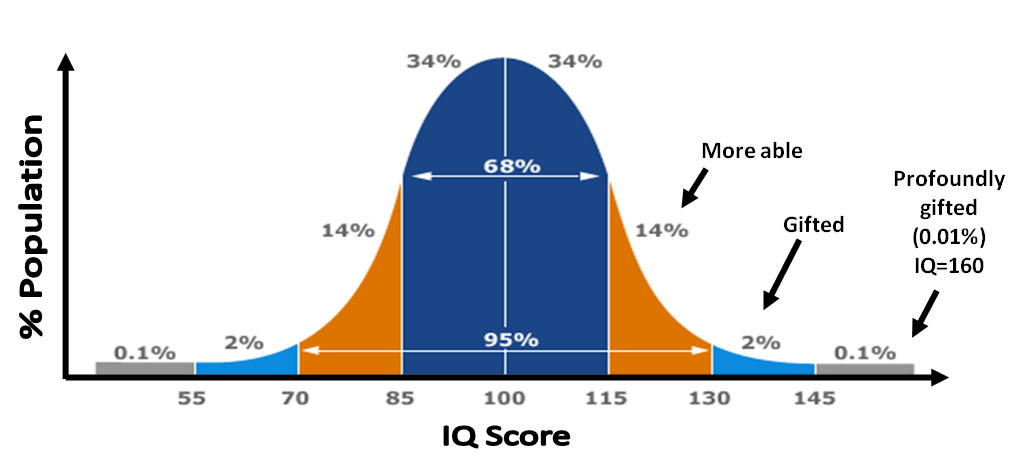

However, a large proportion of these above average ability children are simply ‘more able’ and may not fit the DfE description of giftedness. Gifted and profoundly gifted children are a rarer category of child that can exhibit characteristics that set them apart from more able children. In particular, an asynchronous development of outward ability, where some of their abilities appear significantly above average, and others at or below average, making them potentially more difficult to identify. The abilities listed in this chart below are taken from the DfE checklist for identifying gifted children (1):

This asynchronous split in the personality is strongly evident in the profoundly gifted child. For example, although Albert Einstein never took an IQ test, he showed several hallmarks of being either highly or profoundly gifted, including signs of this asynchronous split. He was a loner as a child, which suggests he was unable to find like-minded peers. He was deeply curious and persistent in his play, in line with gifted children being almost obsessive about their learning. He excelled in science and mathematics classes, but failed other subjects due to skipping lessons he was not interested in. This matches with the single-mindedness of learning gifted children often have. He was often rude to teachers and experienced discipline problems characteristic of the strong views and opinions seen in gifted children. However, he managed to formulate his theory of general relativity whilst working full time in a patent office. This involved finding the answer to contradictions between two of the greatest scientists of the day, Sir Isaac Newton and James Clerk Maxwell about how light travels. Interestingly, many of Einstein’s teachers at schools thought Einstein would amount to little.

This last point is probably the most important in the life of the gifted child and highlights how the asynchronous split in Einstein was perceived by outsiders. From a teacher’s point of view, the gifted or profoundly gifted child shows characteristics than can often make them appear to be below the level of the more able child. Ironically, the more able child is the one who may more likely be identified as gifted, as they appear to be a model student, doing well in exams, integrating well with their peers and being ‘top of the class’ across subjects. Unless the teacher has had specific training in the identification of gifted children, they will likely misidentify both categories of child, with the more able child being wrongly identified as gifted, and the gifted child being wrongly identified as average or even below average in ability.

The teacher may also be concerned about specific behaviours in a gifted child such as their poorer social skills, academic inconsistences, sensitivities, rebelliousness, and other alarming traits. The child from their point of view may be seen as either developmentally behind or has some underlying disorder that requires a diagnosis. This is further compounded by the fact highly gifted children can exhibit character traits that mimic Special Educational Needs (SEN) conditions as described by the DfE:

“There are some subtle links and differences between certain indicators of high ability and other concerns such as Asperger Syndrome (AS) or AD/HD… The difference is subtle and misdiagnosis is relatively common.” (1)

Because giftedness is not classified as a SEN condition there is very limited training, awareness or support for this subset of the school population. Government statistics reveal that there are approximately 8.2 million children currently within the UK education system (2). If 2% of these are gifted (see graph above), this means there are approximately 160,000 or more children that will fit the description of giftedness in schools across the UK. Although the DfE started to produce publications to address this issue, the new government that came to power in 2010 cut all funding for gifted and talented provision within the DfE. As a result, this information is frozen in situ, and has not been disseminated to other government departments that would benefit from it.

From the gifted child’s point of view, their difficulty in finding like-minded peers can make them feel socially isolated in class. Their quick learning and own strong interests can mean they also feel isolated from the curriculum being taught. To attend school every day and not feel engaged with either the children or the lessons, explains why gifted children can often exhibit behavioural problems. This is further compounded by the perfectionism, sensitivity and other personality traits common to gifted children. The lack of training in the range of professionals that may surround this type of child means they can struggle at school without any clear resolution to their problems. It also explains why some parents of gifted children have to move their child to different schools, sometimes several times, and why some have no choice but to educate their child at home.

References

- DfE publication: Identifying gifted and talented learners – getting started.

- DfE publication: Gifted and talented education: Helping to find and support children with dual or multiple exceptionalities.

- Department for Education, Number of schools, teachers and students, 2014.