From the Archive

This article was originally published in the Spring 2016 edition of the Potential Plus UK ezine Ignis

“The Hunger Games” by Suzanne Collins, “1984” by George Orwell, “Divergent” by Veronica Roth and “Brave New World” by Aldous Huxley share with us dystopian worlds where humanity aims for a better society and gets it wrong. It is the standard fayre of many science fiction novels; the need to escape the oppressive nature of the fictional society in which they live which leads individuals to amazing feats. If you want to explore some of these worlds https://best-sci-fi-books.com/dystopian-science-fiction-books/ provides a great jumping off point. However, what if you don’t live in a science fiction novel, but in a real society where you, the individual, is repressed, under attack, suffering? How can you escape? Would you try to leave or to change the society you live in?

What Would Make YOU Leave Your Homeland?

War… famine… a regime different from your own… there are many different reasons for floods of refugees desperately trying to find somewhere for themselves and their families.

We become inured to their plight because we see and hear about it every day, or we temporarily feel an upsurge of sympathy when we view videos like “Most Shocking Second a Day” by Save the Children, which captures what it is like for a child to be torn away from their life. Displaced people are not a new phenomenon. As long as people have had the concept of country, nation, site within a conflict or just natural disaster, we see records of the migration of refugees. The difference now is that modern media brings with it immediacy, a sharing of pain, in a way that has never been possible before; and with that comes fear.

There has been a lot of debate in the media about whether refugees should be welcomed or turned away, whether they will help their adopted country or sponge off it. This is an important issue that you need to decide for yourself. Read around the arguments just as though you were preparing for a debate, look at all the issues for each side. Make sure, when you hear arguments for one side that you understand that this is only one point of view. When you make a choice, be aware of what has influenced you.

Whatever the outcome of the current refugee crises, given the nature of human society it is likely that there will be others within your lifetime. This article by the Washington Post, from 2015, aims to give you a visual representation of selected major global refugee crises since the Second World War. The figures are staggering. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/world/historical-migrant-crisis/

However, mass figures tend to blur together; it is the focus on the individual through personal accounts, fictionalised or autobiographical, that can really help with an understanding of what migration and societal change means. Here we highlight three of them. The first is a fictional account from the time when the Berlin Wall went up overnight, separating Western Europe from Eastern Europe under the Soviet regime. The second is a biographical account, written in free verse, of the life of a Russian émigré to the USA who chose to fight for the rights of women within the society she lived. The last is an autobiographical/ biographical account of the life of three generations of women living in China.

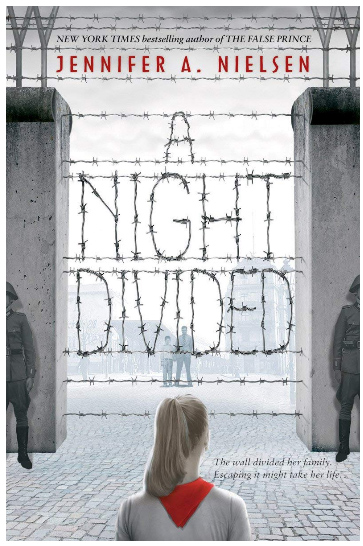

“Mama once said the most wonderful thing about the young is our ability to make things normal. That whatever life does to us, no matter how strange, it isn’t long before insanity seems ordinary, as if upside down is the way things should be. That didn’t make sense to me at first, but over the next four years after the wall went up, I saw it happen more and more. Most children barely notice the wall any longer. They played hoops beneath the eyes of armed border guards in their watchtowers, rolled marbles in the shade of the wall, and learned to do as they were told without asking questions.”

A Night Divided by Jennifer A. Nielsen is an historical novel which examines what happened when the Berlin Wall went up overnight in 1961, splitting families on either side of the divide. Gerta, her mother and brother are stuck on the East German side of the wall, her father and other brother are in West Berlin having gone to look for work. Over the next four years, life gets worse for Gerta and when she sees her father standing on the West Berlin viewing platform miming digging she has to make a choice – will she learn to accept the world she lives in where East German soldiers aim their guns inwards at their own citizens or risk death trying to escape? Aimed at 9-13 year olds, this story is a great introduction to the Cold War and life in East Berlin in the 1960s.

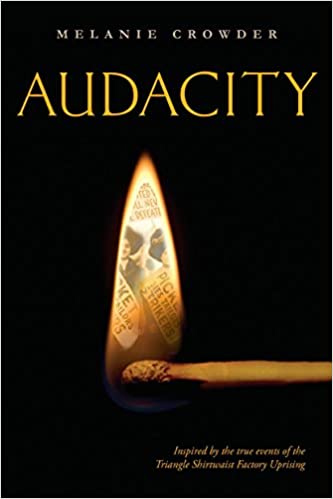

“According to Papa,

a well-educated girl need know no more

than how to sign her name,

read the women’s prayer book,

do a few simple sums,

write a letter to the parents

of her betrothed.

Mama says,

Fifteen is not too young

to be thinking of such things.

But to me

that word

[wife]

is barred and barbed

threatening

to hold me down

when all I want

is to stretch my wings

to ride the fickle currents

beyond the reach

of any cage.”

Audacity, by Melanie Crowder is the fictionalised account of the early life of Clara Lemlich, who emigrated from Russia to the USA at the turn of the twentieth century. Her fight for equal rights for women, firstly within her own family and the society in which they lived (Russian Jewish), and then within the atrocious working conditions of Lower East Side Manhattan factories, led to a strike of 20,000 women in the garment injury in New York in 1909. This is the largest strike by women in the history of the United States of America. The story is fascinating; the use of incredibly beautiful and powerful free verse to tell the story really makes this book stand out.

“In 1964, Mao had denounced cultivating flowers and grass as ‘feudal’ and ‘bourgeois’, and ordered, “Get rid of most gardeners.” As a child, I had had to join others in removing the grass from the lawns at our school, and had seen flowerpots disappear from buildings. I had felt intensely sad, and had not only struggled to hide my feelings, but also blamed myself for having instincts that went against Mao’s instructions, a mental activity I have been brainwashed to engage in, like other children in China. Although by the time I left, one could express love for flowers without being condemned, China was still a bleak place where there were virtually no house plants or flower vendors. Most parks were brutalized wastelands.”

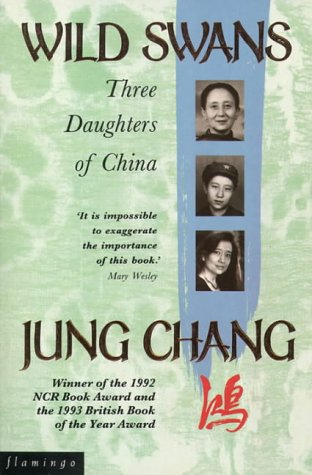

Wild Swans: Three daughters of China by Jung Chang is a personal history of 20th century China through the lives of three generations of women. Jung Chang’s grandmother had her feet bound as a child, and she was given to a warlord general as a concubine. Jung Chang’s mother was an activist in the Communist Party during the Chinese civil war and she and her husband became high ranking party officials. Questioning of Mao and the suffering of the Chinese people led to her parents being denounced and tortured and Jung Chang being exiled as a peasant to the Himalayas. Following periods as a ‘barefoot doctor’, a steelworker and an electrician, she was considered rehabilitated and was sent as a student to London. At the age of 30 she became the first person from the People’s Republic of China to receive a doctorate from a British university. Jung Chang remained in England. Her tale is immensely moving, and at times her memoirs can be quite harrowing as it enlightens the different regimes that existed in China last century. The book has sold over 13 million copies in 37 languages. However, it remains banned in her native China.

So would you try to leave or to change the society you live in? Contact us with your opinion at focus@potentialplusuk.org

About the Author: Geraldine Glover is Potential Plus UK’s Community Information Coordinator. She is a Chartered Information Professional with a background in editorial work and information science. She is the mother of two children with high learning potential.